'A bandaid': Experts say delaying evictions helps, but doesn't solve the COVID-19 housing crisis

- Emily DiSalvo

- Oct 31, 2020

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 7, 2020

COVID-19 cost hundreds of thousands of jobs in Connecticut, creating a massive housing crisis in a state that U.S. News and World report calls the fifth wealthiest in the country.

Fifteen percent of Connecticut of renters are not caught up with payments and their housing security lies in limbo after a series of eviction moratoriums have bought these renters time, but not a real solution.

According to Justin Farmer, a member of the Hamden Legislative Council, this is 170,000 people who are eligible to be evicted in January.

"It's an important band-aid," said Cathy Zall, executive director at the Homeless Hospitality Center in New London, Connecticut. "I don't think we would be better if there was no moratorium. But like all of those things, it sort of depends what we are doing while we are benefitting from the band-aid."

Reporting from WNPR cites a survey from May that indicates that state eviction rates were likely to jump from 4% to 7% this year because of the pandemic.

"If you evicted everyone in the city of Bridgeport, that is how many people we are talking about that could potentially be homeless," Farmer said.

Currently, tenants who failed to pay rent due to financial hardship caused by COVID-19 are spared from paying until Jan. 1, under Governor Lamont's latest executive order.

This is not the first time Lamont issued an executive order about evictions. Since the pandemic started there have been several moratoriums. The original one was set to expire in September, the second in October and the third now at the end of the year. The renewal of the moratoriums angered landlords, many of whom feared going out of business without monthly rental payments.

“It’s sad they keep using the landlords to shoulder public benefit,” John Souza, president of the Connecticut Coalition of Property Owners said. “It’s not really fair to us."

Lamont said he made the decision because of the high unemployment numbers as a result of COVID-19.

Housing advocates say extending moratoriums isn't a strategy and Lamont and his administration lack a long-term solution. According to Erin Kemple, executive director at the Connecticut Fair Housing Center, Lamont is hoping that the federal government will step in to help. On a call with Lamont, Kemple asked what the "end game" was going to be if the federal government doesn't provide funds.

"The answer was, 'Well if we get to the end of November, beginning of December and it hasn't happened, we will talk about it then.'"

Kemple doesn't think Lamont's best case scenario is likely. More likely, she thinks Connecticut is about to having a housing crisis on its hands.

"I don't think we can afford to wait that long," Kemple said.

The current crisis involves a backlog of unpaid rent. Renters have been excused from their payments for the past several months. The state has offered $40 million from the Temporary Rental Housing Assistance Program (TRHAP), which experts estimate will only help 10,000 renters.

As of October 2020, renters in the U.S. owe roughly $25 billion in back rent according to Moody's analytics. Zall estimates Connecticut renters owe about $300 million.

"This is not something that the state of Connecticut, which needs to have a balanced budget will be able to address," Zall said. "There are state programs out there, millions of dollars, but it is going to take a massive investment to help people dig out."

Despite the waiver on paying rent, Melissa Marchial, a staff attorney at Connecticut Fair Housing said some landlords are still trying to get renters to pay up.

"This doesn't mean landlords aren't telling tenants that they need to leave and harassing them to get out," Marchial said. "A lot of renters aren't aware of what protections are available to them."

The Connecticut Fair Housing Center is communicating with tenants about the protections that the moratorium affords to them.

The question on many renters minds is "Can my landlord do that?" Organizations like CT Fair Housing and the CT Coalition to End Homelessness hosted several virtual town halls to walk renters through different hypothetical situations and the legal rights that coincide.

The broader problem

Like so many other problems caused by the pandemic, this housing problem isn't impacting all people equally. Those on the brink of facing eviction are disproportionately minorities who live in Connecticut's major cities. Of the 15% of Connecticut renters who missed rent payments, 23% of Black renters missed payments, whereas only 10% of white renters missed payments. Experts hope the crisis COVID-19 created for renters will move politicians and policy-makers to consider broader structural changes to affordable housing.

Income inequity in Connecticut is even greater than the country as a whole.

"Connecticut, one of the wealthiest states in the U.S., had the third-highest income inequality in the nation in 2015 — when the average income of the top 1% was 37 times greater than that of the bottom 99%," reads a report from the Connecticut United Way.

Desegregate CT, a coalition of people an organizations committed to change state land use laws to end segregation and provide more affordable housing in Connecticut, entered the legislative discussion in June. The group was in the works before COVID-19, but came to fruition right in the midst of it.

Robby Hill, an undergraduate student at Yale and partnership coordinator for Desegregate CT, pointed out how despite many people saying that the virus doesn't discriminate, it does.

"People who are living in affordable housing are disproportionately people of color, Black people, single mothers and to me it feels like it is the least advantaged people who are getting the worst hand," Hill said.

Desegregate CT is advocating for legislation that would reorganize zoning and land use laws in the state so that land outside of the cities that are already concentrated with renters and affordable housing, can be zoned for affordable housing and multi-family homes.

"The vast majority of affordable housing exists in major cities that are already pretty economically deprived," Hill said. "Hartford, New Haven, Bridgeport, Waterbury and I think there is some reason for that. There are a lot of factors that go into social mobility that are not just the house you have... it's this mixture of factors that you can't address by constructing another 10-story building in the east end of Hartford."

Wealthy towns in Connecticut like Westport, for example, have tight zoning regulations to ensure that developers can only build single-family homes. When a developer came to Westbrook in 2014 hoping to build a mixture of single and multi-family homes on a 2.2 acre lot, he found that the lot was only zoned for four single-family homes, according to ProPublica. This developer was hoping to build homes for 12 families.

"If we reform our zoning codes and allow people to have this access across Connecticut so they are not confined to urban centers and have better access to education, our hope is that in the long run this will not just be about housing, but it will be about a complete transformation of lower-income housing in Connecticut," Hill said.

The solutions that Desegregate CT propose could have helped to find people more sustainable housing prior to the pandemic, but it was too late. Now, eviction is a real possibility for many families that were already struggling prior to the pandemic.

So what now?

Now that COVID-19 has occurred within the existing system of poverty and segregation, Connecticut and the country as a whole have a crisis on their hands. If the federal government does not intervene, what happens next?

Zall said shelters have resources to help those who are currently homeless, but will fall short if thousands are evicted in 2021.

"Somebody has to give some very hard thought about how to find an equitable way to provide assistance so we don't have a massive eviction," Zall said. "That is not in anyone's interest. Not in the tenant's interest, not in the landlord's interest — it's not in the interest of the public or the homeless response system."

Rental assistance is what Zall is referring to as the "front line" to protect against evictions, but Cancel Rent CT, an organization that formed in May as a result of COVID-19 , is calling for a more drastic solution.

"Canceling rent is not just the only moral solution, it is also the only solution that matches the scale of this crisis," wrote Ashley Blout, Co-Deputy Director of CTCORE – Organize Now! in the CT Mirror. "Our social safety nets are too underfunded and outdated to handle the enormity of this moment. What is the point of being one of the richest countries in the world if we can’t care for our citizens? We are in a state of emergency. It’s time to cancel rent."

Cancelling rent and then providing funds to landlords would help deal with the backlog of rent that thousands of people will simply not be able to pay, even after the pandemic.

Prominent political figures like Senator Bernie Sanders have made similar requests.

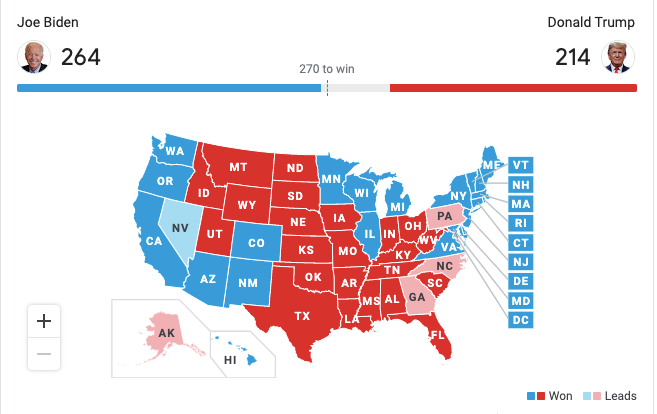

According to an article from Market Watch, Joe Biden has indicated he also believes this to be the best solution.

“There should be rent forgiveness and there should be mortgage forgiveness now in the middle of this crisis,” Biden said during his appearance on Good Morning America. “Not paid later, forgiveness. It’s critically important to people who are in the lower-income strata.”

On the local level, long-term housing solutions are on the mind of officials like Farmer.

"The federal government needs to stop doing this public-private partnership," Farmer said. "The federal government needs to actually fund housing."

Farmer also suggested the establishment of a state bank for renters to draw funds from, rather than asking big banks for loans.

"We would be pooling our own resources and we would keep interest rates low," Farmer said. 'We know housing is a high risk, but the way out of many of these issues is fundamental change."

Comments